This post was updated in November 2025. See here for more on Wrocław.

Ya girl is publishing a good old-fashioned travel blog! I’m attempting to write again(ish) on a more consistent basis (melting face emoji). Taking a break from memorialization and historical memory research — although there’s a bit here of course — and writing about snacks and wanderings: my bread and butter (or in this case pierogi and Tyski) of most requested topics (here for the food pics, I feel you).

Last year Chris and I had the opportunity to visit the gorgeous city of Wrocław, located in western Poland. Pronounced “Vrohts-wahf“, the city was and is sometimes still referred to as Breslau due to its German past. I loved this overview of the different ways to pronounce the city here.

We traveled to the delightful city of Wrocław via Berlin during July and November; just a couple of hours (direct! What a treat!) from Germany’s capital (and one of my favorite cities — that enormous blog post has been simmering in my brain for literal years at this point) and a few hours to Kraków. With only a few days in the summer and just 24 hours during the winter holiday, I wish we had more time to explore but loved our wanderings here.

Wrocław has been on my list for years as Chris visited the city a couple of times for work when we lived in Hungary and always had a great time. This city really is Chris’s happy place – a large central square with a ton of outdoor seating and space, pierogi in all forms easily accessible, cheap locally brewed beer, and even colder Polish vodka — it was a lot of fun for me to experience the city with Chris as our guide!

Even though our time was short, I’m so grateful to experience both the summer and winter Wrocław vibes. While the city is absolutely lovely in the warmer months — the main square is home to a number of festivals and events — I was completely blown away by their December holiday setup. I’ve traveled to a ton of Christmas markets all over Europe and whoa, Wrocław throws down.

Photo and Text Source

This post references genocide, the Holocaust, and sexual assault. Please take care of yourself ❤

Where are we?

As with many European cities, the history of Wrocław is long, complicated, and intertwined, so I hope to provide a little context and a brief overview here. Historically the center of the Silesia region (an area of Central Europe today mostly comprising Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic), the first instance of the Polish city — “Vratislavia” — occurred in the 10th century. Ethnic Germans became the dominant demographic here in the mid to late 1200s as the area passed between Poland and Bohemia.

Following Austrian Habsburg rule and the Thirty Years’ War, war and plague decimated the population of Wrocław by half. In 1741, “Breslau,” as it was known, fell under Prussian rule; they allowed both the Protestants and Jewish communities to practice their religion freely. In the 1800s, the city prospered, and when the German Empire consolidated in 1871, Breslau was the third biggest in the empire (after Berlin and Hamburg) with the third-largest population of Jewish people in Germany.

After avoiding major damages during WWI, Wrocław’s landscape and population changed immensely during the Second World War (even as the city remained far from the front lines). During Adolf Hitler’s rise, the city was one of his largest areas of support and considered a “model German city” for Nazi Germany. Beginning in 1938, state-organized violence against people of Polish and Jewish descent began; Jewish institutions including schools and synagogues were destroyed, and deportations started in 1941. The first transport forcibly deported the once-citizens of the city to Kaunas (now Lithuania) where they were murdered. Subsequent deportations from the Wrocław Nadodrze station took place, sending Jewish people to labor and concentration camps across Nazi Germany. Polish, Russian, Italian, Chinese, Belgian, and Czech people were among the thousands imprisoned and killed in camps built in the city.

As refugees from other parts of Europe swarmed to this area, the Nazis declared the city to be a closed military fortress — Festung Breslau — not allowing anyone to enter or leave in an effort to keep the incoming Soviet army from seizing control.

With their stronghold appearing grim (the Nazi soldiers were a mix of veterans and Hitler Youth that were not provided proper weapons or vehicles) the Soviets easily began to shell the city. Nazi Commander Karl Hanke refused to evacuate civilians (many of whom were refugees from other areas of Europe) until January 19th, 1945, a decision that left evacuees one option — leave on foot. With below freezing temperatures, around 18,000 civilians froze to death. After both sides suffered heavy casualties and the city was largely burned to the ground, a peace agreement was signed on May 6th, the final Nazi city to surrender to the Soviet Army.

The siege left the city in ruin with over 170,000 civilians dead. As the Soviets gained control, they also left their mark of violence and terror on the small population that remained.

“It’s estimated that approximately two million German women were raped by Red Army soldiers, and Breslau proved no exception as marauding packs of drunken troops sought to celebrate the victory. With all hospitals destroyed, and the city waterworks a pile of ruins, epidemics raged unchecked as the city descended further into hellish chaos. Historical figures suggest that in total the Battle for Breslau cost the lives of 170,000 civilians, 6,000 German troops, and 7,000 Russian troops. 70% of the city lay in total ruin (about 75% of that directly attributed to Nazi efforts to fortify the city), 10km of sewers had been dynamited and nearly 70% of electricity cut off. Of the 30,000 registered buildings in the city, 21,600 sustained damage, with an estimated 18 million cubic metres of smashed rubble covering the city – the removal of this war debris was to last until the 1960s.”

In Your Pocket. 2022. “Festung Breslau: The Siege of 1945.” Available here.

In February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin effectively drew new borders in Europe, giving Breslau—now Wrocław—to Poland. As efforts to “de-Germanize” the once shining example of Nazi Germany’s hopes, a majority of the ethnic German population was forcibly pushed out with German language and signage scrubbed from the remaining buildings. During this time, thousands of Polish and Slavic refugees flooded into the city from other areas of war-torn Europe, including Lwów (now present-day Lviv, located in Ukraine).

From the late 1950s onwards, Wrocław became one of the main economic, cultural, and academic centers of Poland. Workers went on strike alongside the Gdańsk Solidarity Trade Union led by Lech Wałęsa, who would eventually become Poland’s first freely elected president after WWII. In 1990, the city restored its historical coat of arms in an effort to symbolize the embracing of its history, including the years under German rule. Wrocław also earned the titles of European Capital of Culture and UNESCO City of Literature in 2016.

Sites:

Rynek (Old Town Market Square):

Christmas Market:

While aspects of Soviet architecture lay behind the façade of the Old Town buildings, many other areas of the city’s landscape are visibly dominated by socialist realism buildings. Constructed in war-torn countries located in the USSR, these buildings quickly housed refugees and workers. Many of the districts outside of Old Town reflect a mix of 75 years under German rule and Soviet design.

Nadodrze District:

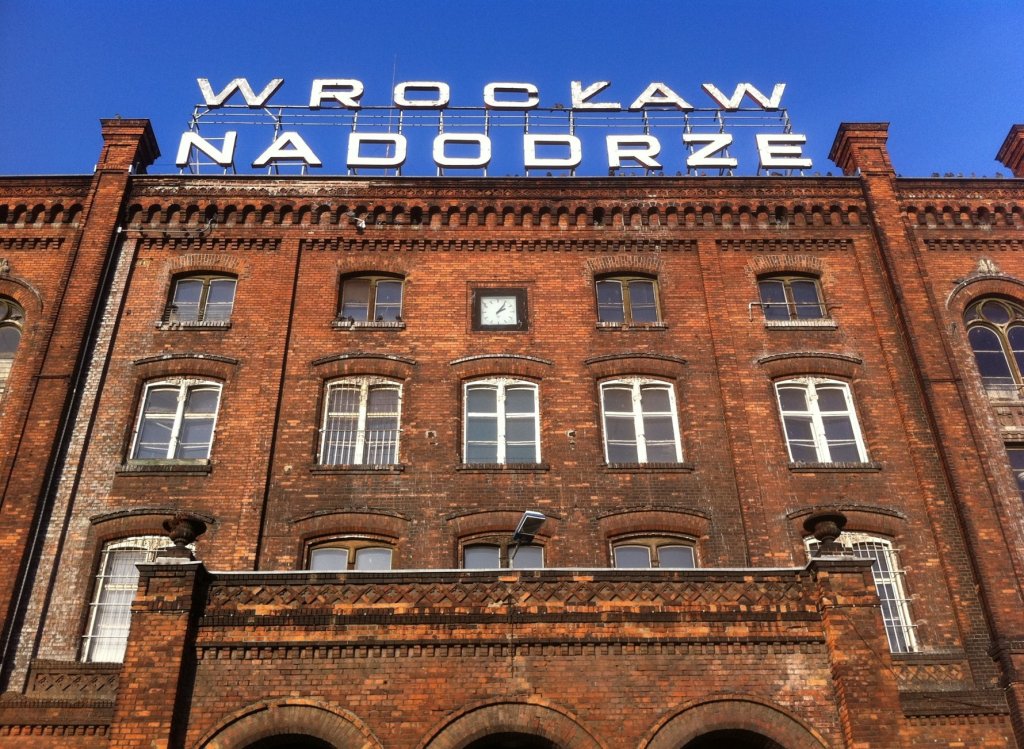

Dworzec Nadodrze (Nadorze Railway Station):

The station with the its iconic neon sign. When we visited in 2022, the sign had been removed until the building can be restored (it was recently sold just a month before our time there in July).

Designed by Hermann Grapów and completed in 1868, the station miraculously survived the war and is still in use today.

Today, a small plaque near the entrance of the station is the only indication of what occurred here. The memorialization was started (and continued to fight for fifteen years) by Mrs. Rita Kratzenberg, who was one of the thousands deported here and of the few who survived.

Heat Power Plant:

Pomnik zesłanców na Sybir (Monument to the Exiles to Siberia):

Hundreds of thousands of Poles were deported to Siberia. While an accurate total number will most likely never be found, it is estimated that 1.5-1.7 million were forcibly sent into the USSR.

Restaurants:

Restauracja pod Fredrą:

Pierogarnia Stary Młyn:

Pierogarnia Rynek 26:

Chleboteka:

Poko Bakery & Cafe:

Pochlebna:

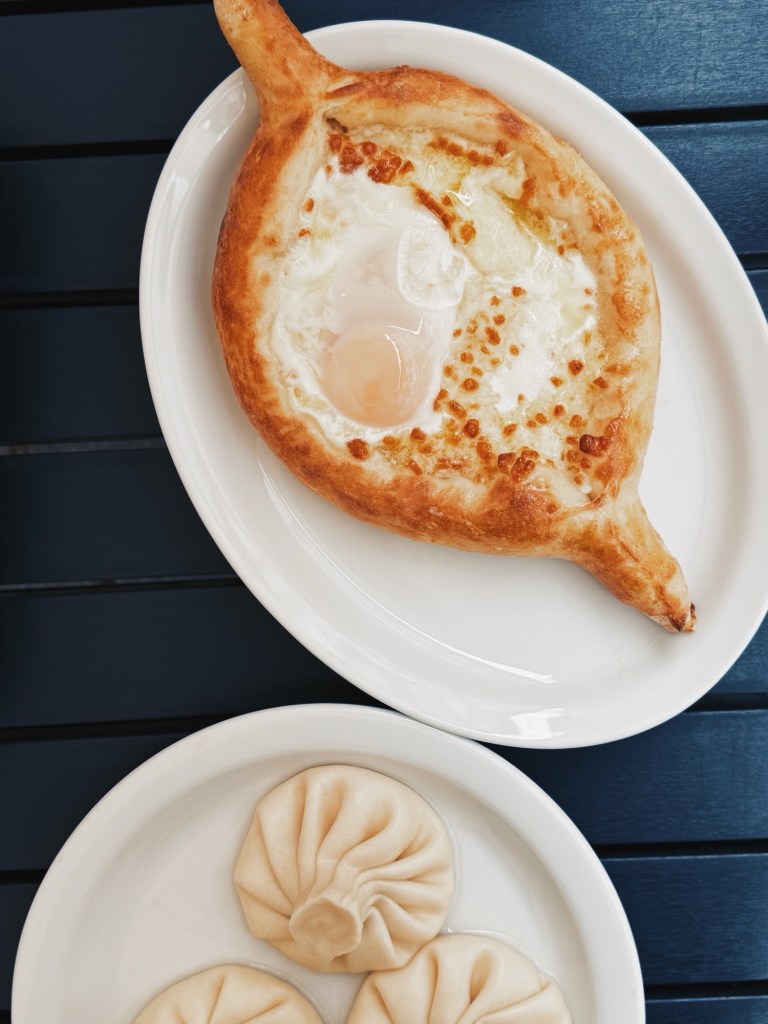

Puri Georgian Bakery:

Chinkalnia:

Dot Coffee:

Bars & Pubs:

Kontynuacja (now closed 😦 ):

Lot Kury (now closed 😦 ):

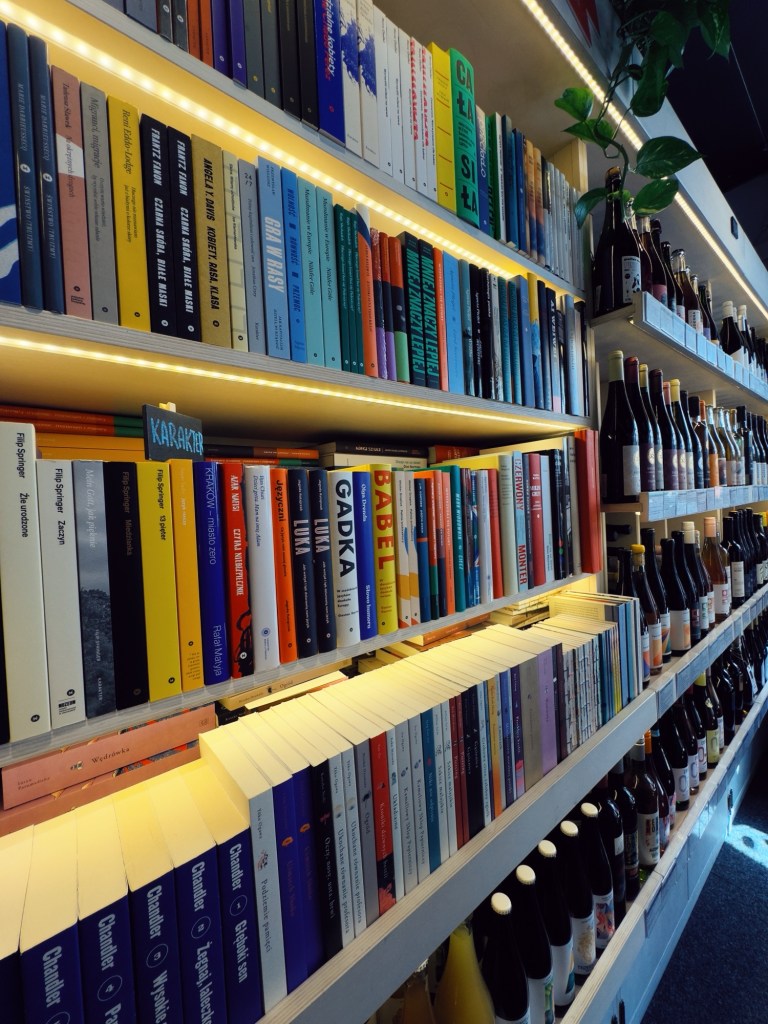

Literatka (now closed 😦 ):

Cocofli:

🤍

Currently:

Reading: No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating ( Alicia Kennedy )

Watching: Another Period ( Paramount + )

Listening: The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight ( Andrew Leland )

Further Information & Sources Cited:

Ariet, Andrea. 2018. “Nadodrze, A Forgotten Area with a New Lease of Life”. Andrea Ariet. Available here.

Ariet, Andrea. 2018. “Nadodrze Railway Station, the Odra’s Gate.” Andrea Ariet. Available here.

Art Transparant. 2016. “Stanisław Dróżdż: Text Paths.” Available here.

In Your Pocket. 2022. “Festung Breslau: The Siege of 1945.” available here.

In Your Pocket. 2022. “Phoenix from the Ashes: The Rebuilding of Wrocław.” Available here.

In Your Pocket. 2023. “Wrocław History.” Available here.

Information Portal to European Sites of Remembrance. 2022. “Memorial Plaque for the Deported Jews of Breslau.” Available here.

Luxmoore, Matthew. 2018. “Poles Apart: The Bitter Conflict Over a Nation’s Communist History.” The Guardian. Available here.

Napieralska, Zuzanna and Elzbieta Przesmycka. 2020. “Residential Districts of the Socialist Realism Period in Poland (1949-1956).” International Congress on Engineering — Engineering for Evolution. 680-691.

Rybicka, Urszula. 2022. “Jewish Wrocław.” Available here.

University of Illinois Library. 2022. “Soviet Deportation of Poles During World War II, 1939-1945.” Available here.

Vagabundler. 2023. “Poland: Streetart Map Wrocław – Urban Art Archive and Graffiti Tracker.” Available here.

Wroclaw Guide. 2022. “Nadodrze Neighborhood Map.” Available here.

Leave a comment