This March I spent a day and a half exploring the lovely Swiss city of Basel. Less than a five hour ride by train, I spent my time exploring the city’s beautiful landscape, mueseums, and of particular interest to me, the colonial legacy within Basel.

Mirroring my wandering through the city, this meandering post will include (a lot!) of photos and text on the colonial history of Basel, spaces related to that legacy, sites, and of course, my favorite bakeries. I absolutely adored my time here and hope I have a chance to explore longer than my 36 hours (especially because my favorite Swiss vegan bakery — located at the train station! What a delight! — opened a mere four minutes before my train to Germany departed. A shame).

My hope here is to talk more on the lesser known aspects of the city, portions of the collective history that are omitted from the dominant narratives. These events were vital to building Basel’s wealth even if they are largely absent in the discourse. I’m interested in how these colonial legacies can be seen in the city’s landscapes and museums and how we can have larger conversations on the impacts for both the communities exploited and Switzerland as a whole.

This (very long) post discusses colonialism and genocide so please take care when reading ❤ I also want to note the absolutely incredible work by Claske Dijkema in not only researching the colonial legacies of Basel, but creating a map so I could develop my own one person tour.

While I was there, I visited the Museum of Culture and its Memory — Moments of Remembering and Forgetting exhibit, which included the following:

“Which moments become imprinted in our memory? What do we dismiss? How do we commemorate and pass on events that are relevant to society? Collective memory — Remembering and forgetting are two mutually dependent sides of memory. Shared experiences and memories are fundamental to the self-conception of people and groups. However, reference to the past are never static, on the contrary, they are continually being negotiated and appropriated. Collective memory is composed of different, often contradictory positions and perspectives which impact on how and in which form certain events are memorized and visualized, or withheld and denied.”

“Memory — Moments of Remembering and Forgetting” 2024. Museum of Culture Basel. Available here.

Where are we?

Located in northwestern Switzerland (just over the German border) and on the river Rhine, Basel is the third most popular city in the country. Known for its museums and the University (the oldest in Switzerland) Basel is often considered the cultural capital of the country.

After falling under a number of ruling governments, including the Celts and Romans, the Alemannic and Frankish settlement around the old Roman castle grew during the 6th and 7th centuries. In 843, Basel was transferred to West Francia before being given to East Francia in 870 and was completely destroyed by the Magyars just forty years later. In 1032, the rebuilt town was merged under the Roman Empire, becoming the medieval city its known for by the 11th and 12th centuries.

The University of Basel was founded in 1460, bringing a number of scholars and academics to the city, making Basel a center for humanism and even book printing. From 1814-1815, Switzerland gained independence from Austria during the Congress of Vienna and boundaries were established that created the country we see mapped out today.

Switzerland was “neutral” during the Second World War, although this still led to a number of atrocities including harsh policies toward refugees, turning away 30,000 Jewish people fleeing Nazi Germany in 1942. The Swiss also continued trade with the Nazi regime including coal for steel and guns; the two countries also traded in art, including paintings stolen from Jewish families and art galleries. One of Basel’s most famous museums, the Kunstmuseum, settled a restitution case in 2020, paying $2 million for 200 pieces that once belonged to the renowned Jewish museum director, Curt Glaser. The works were purchased by the museum at a 1933 auction. During this time, Swiss bankers also accepted gold and currency stolen from Jewish Holocaust victims, depositing them for Nazi leadership officials.

I know that I am highlighting many of the bleak aspects of this city’s history, but my hope is to mention many of the historical inaccuracies under the blanket term “neutrality” that are omitted from most narratives, particularly genocide.

Colonial History & Sites of Switzerland:

Basel and Switzerland are spaces that I love to research in that their ties to colonial exploitation — and the wealth built from these endeavors — are present, but are just more difficult to uncover. Unlike many of its European neighbors, Switzerland did not ever own colonies, but the country and many of its citizens profited greatly from this work. A combination of an increase in silk, weaving, and dying of textiles, along with investing in the triangular trade, evolved into the lucrative pharmaceutical and banking industries that the city is known for today. Colonialism also had a direct impact on the development of the museums and university that helped Basel become the country’s cultural capital.

Let’s break it down by sector(ish). Like most colonial legacies, this story is an entanglement of different areas and wealthy families.

Textiles:

The 17th century held an enormous boom in textile wealth for Switzerland. The popularity of “Indiennes” fabrics (colorful printed cotton) were originally printed by people in India until Dutch and British manufacturers — through mechanization — began producing similar fabrics for cheap, undermining the Indian industry. French Protestants, fleeing the country due to religious persecution, began establishing textile factories on the Swiss border, bringing wealth from this trade into the Swiss economy and laying the foundation for industrialization of the country. However, this industry was directly connected to the triangular trade as these fabrics were sold in West Africa as a bartering currency in exchange for enslaved people shipped to the Americas.

Spiegelgasse 4

Today this address is home to the BKB, but it was once the location of Haus Segerhof, an enormous home built in 1789 by Christoph Burckhardt-Merian, the son of Christoph Burckhardt-Vischer. Their company, Christoph Burckhardt and Co. was founded and operated here, where they traded raw cotton and Indiennes supplies, exchanging the materials for enslaved Africans in the triangular trade. The company made a fortune and reinvested these funds into merchant ships, including the son’s new company, Bourcard Fils & Cie. The family continued to invest and profit from ships even after the trade was banned by the British in 1808. These two companies were part of 21 expeditions in the purchasing and selling of enslaved people from 1783-1818; an estimated 7,350 enslaved Africans (1100 died during the brutal trip) were brought to the Americas during this time.

“In an interview with the local newspaper Bajour, Veit Arlt of the Center for African Studies explains that what really benefited the Basel economy was the fact that capital could circulate across borders and then be reinvested on a local scale. The textile industry made possible by the triangular trade and has in turn offered Basel a steady economy that helped build the chemical industry as we know it today.”

Bonvin, Leah. 2020. “Haus Sergerhof”. Colonial Entanglements in Basel. Available here.

Financial investments also show the connection between funding and the triangular trade. Swiss entrepreneurs invested in ships that forcibly brought more that 170,000 enslaved Africans to the Americas; the South Sea Company, a British firm that traded enslaved people, was funded by Swiss city Berne, the largest shareholder for the company at the time. Studies show Swiss citizens were also directly involved in transatlantic slavery. Individuals owned plantations, worked on ships, and brought enslaved people back to Switzerland. The country’s own “founding father” Aldred Escher is connected to chattel slavery; he and his family owned a Cuban coffee plantation that enslaved more than 80 people.

“Trade with Saint Domingue became increasingly difficult because slaves there dared to rebel. Somewhat by chance, [Christoph] Burckhardt acquired the ship with the significant name ‘L’Intrépide’, the daring one. The ship became a tragedy for the crew and the ‘cargo’, and for Burckhardt it was an economic fiasco. When it arrived in Nigeria, the ship had already been damaged by storms and had been tied back. Instead of 400 as planned, the captain only bought 240 male and female slaves, for which he bargained for a full year. All of them bore the brand: LTP, short for the name of the ship. The hygienic conditions while waiting must have been terrible. 77 prisoners died during the purchase negotiations, as well as six crew members. Another 64 slaves died of smallpox and diarrhea during the crossing to Cayenne. What was particularly annoying for Burckhardt was that he was insured against disfigurement due to mistreatment, but not against death due to ‘natural’ circumstances.”

Rosh, Benjamin. 2020. “How a A Basel Daigler Traded in Slaves and How his Descendants Wanted to Cover Everything Up.” BZ Basel. Available here.

Peter Merian-Weg 8

Located one stop from Basel’s main train station is the platform created for the enormous buildings that comprise Peter Merian Haus and Jacob Burckhardt Haus. And by enormous, I mean, seriously huge and also difficult to navigate from the stop unless you are specifically here for these spaces. The Merian Haus was established in 2011; Burckhardt Haus in 2009.

Münchensteinerstrasse 1

Christoph Merian was the son of Christoph Merian-Burckhardt (Senior) and grandson of Christoph Merian-Hoffmann (I know, phew its a lot to keep track of). Christoph Merian-Hoffmann established Frères Merian (along with his brother) in 1788, based in Basel, and traded in colonial goods and banking transactions. Due to his enormous wealth, he was able to purchase large amounts of land in Switzerland. His son, Christoph Merian-Burckhardt (senior) also worked in raw cotton, banking, and shipping, including investing in the industries. He gifted this land (among a great deal of inherited wealth) to his son, Christoph Merian. Christoph Merian married Margarethe Burckhardt (herself a descendent of the Burckhardt family, known for their colonial legacy) and the couple established the Christoph Merian Stiftung (Christoph Merian Foundation), an organization seeking to build public parks, social housing, museums, and other social projects. Today, the foundation includes 301 initiatives across the city, 900 hectares of land, 5 organic farms, and 390 buildings, all wealth stemming from Christoph Merian-Hoffmann.

“They remind us how those powerful families and their wealth (mainly gained through colonial activities) shaped Basel and how the city’s urban space is still imbued with their influence today. For example, the construction of the Peter-Merian Haus required the building of the Peter-Merian tram stop and the Peter-Merian Weg for pedestrians and bikes. This shows how those wealthy families are still actively being represented in the public space of Basel and raises other questions: Who is remembered in the public space, and who has the power to decide which figures deserve to be remembered?”

Bonvin, Leah. 2020. “Merian Haus and Jacob-Burckhardt Haus.” Colonial Entanglements in Basel. Available here.

Schlossgasse 9

John Deucher purchased Bottmingen Castle in 1720. A successful speculator, he became even wealthier after investing in the company owned by his friend, John Law. First known as The Mississippi Society, then Compagnie des Indes, this organization was established as a competitor to the English and Dutch colonial operations in the East Indies. They first helped establish a colony in Louisiana (bringing 800 people to the colony in 1718, doubling its European population) before controlling trade between Europe and India. Law’s company also transported nearly 3,000 enslaved people to the Americas.

Swiss entrepreneurs and businesses also engaged in other commodity trading including silks, cocoa, and raw cotton. After the abolition of slavery in the United States, many companies turned to India exclusively for raw cotton and textiles. As the country was a British colony at the time, Indian farmers grew cotton rather than food crops, resulting in food insecurity and famines across the continent. A majority of cotton was sent to Switzerland — not Britain — although Swiss companies including the firm Volkart Bros. utilized connections with textile mills in Manchester, known as “Cottonopolis”.

Rheinsprung 18

An enormous mansion in the heart of Basel’s Old Town (it’s so large you can see the building from the other side of the river), this palace was built from 1763-1770 for the Sarasin brothers (Lukas and Jakob), two extremely successful Swiss silk ribbon manufacturers, as a space for their business empire. Established by their father, Hans Franz Sarasin, the business made the family and city of Basel extremely wealthy. They imported silkworms and silk from mostly Japan.

Spalenberg 22

The former colonial goods store in Basel’s beautiful Old Town shows the city’s colonial legacy right in the built landscape. Emil Fischer opened this store in 1877 and ownership followed to his son, Emil Fischer Jr., who saw the operation expand to five stores by 1914. This mural was painted by Burkhard Mangold from 1915-1918 and is very much a stereotypical representation of the cultures where the goods sold here were derived from.

In 1815, the Basel Mission also became part of Swiss indirect (and yet, pretty direct) connections to colonialism. Funded by wealthy Swiss families — including the Burckhardts, who owned a colonial goods trading company mentioned above and that we’ll see later on — a mission was established in southern India to convert “non-believers” to Christianity, as well build factories and mills for Indian converts. In 1859, the board of the Basel Mission established the Basel Mission Trading Company, one of the first stock corporations in the country, with over 6,500 employees by 1916. Known for its chocolate industry, Basel’s chocolate has a direct connection with colonial pursuits. The network established by the Mission Trading Company guaranteed the shipment of cocoa from the Gold Coast (today: Ghana) by the British to Switzerland during WWII. As noted later, these missionary establishments also resulted in the stealing and transportation of local and Indigenous artifacts and plants back to Basel’s museums.

Missionstrasse 21

There are efforts by the organization to discuss its colonial past including exhibits and a Mission and Colonialism in Basel City Tour, asking “What complications from the past continue to have an impact today?“

Pharmaceuticals:

“Colonialism without Colonies” connects the city’s recent past with its current major industries. The city is the center for the pharmaceutical industry; in Switzerland, from 2010-2020 the sector grew by 10.7% each year and despite the Covid pandemic, in 2020 the gross value added was 36.8 billion CHF (40.6 billion USD). Pharmaceuticals in Basel alone saw 24.7 billion CHF (27.25 billion USD) gross value added in 2020. A report on the importance of the industry to the city states that:

“The chemical-pharmaceutical industry in the Basel region has a long and successful history. Today, Basel is by far the largest pharmaceutical cluster in Switzerland and one of the world’s leading life science locations. The Basel pharmaceutical cluster also occupies an exceptional position in terms of the importance of the pharmaceutical industry for the regional economy… Pharmaceutical industry is the flagship of Basel’s life science center.”

Pharmaceutical Hub Switerland. 2022. “Pharmaceutical Hum Switzerland 2022 Basel Region.” Interpharmaph. Available here.

Spalengraben 8

Established in 1589, the Basel Botanical Garden is one of the oldest worldwide. Pictured here is the Garden’s Victoria House, modeled after the lotus flower. The plant’s discovery is credited to Robert Schomburgk in Britain’s only South American colony (present day-Guyana) and was named for Queen Victoria, herself an avid proponent of colonial expansion. The lotus has a number of names in Spanish and Indigenous backgrounds, including the name Irupé by the Guarani Indigenous community. Many plant and animal species are named for the Europeans that “discovered” them and there is currently a movement to rename them. In 1842, the Botanical Garden (and many of its plants derived from European colonies) was relocated (financed by donations from Basel’s richest, including the Merian and Burckhardt families).

The foundation of this enormously profitable industry lies in colonial exploitation. Scientists and pharmacologists interested in plant medicine traveled to colonies in the British and Dutch empires including India, South-East Asia, West Africa, and South America, interacting with Indigenous populations, their landscapes, and their plants used for medicinal purposes. Often, plants were brought back to Basel, studied, and classified to Europeans standards. Not only were “breakthroughs” attributed to European scientists without proper credit given to the communities these were stolen from, but new advances in medicine also allowed for further colonial pursuits.

There are multiple examples in Basel’s incredible Pharmacy Museum, a small and interesting museum I visited while in the city. I highly recommend walking through the building (half off entrance fees with the BaselCard) that is part of the University of Basel.

Totengässlein 3

The Pharmacy Museum of Basel contains one of the most comprehensive and impressive collections of pharmaceutical artifacts in the world. Opened in 1924, University of Basel pharmacist and historian Professor Josef Anton Häfliger donated his private collections to the university and designed the museum for both instruction and and public use.

In an interview about the museum’s collections, the main room of the Pharmacy Museum:

“exhibits remedies, drugs and medicinal objects of the three kingdoms (mineral, vegetable, animal/human), folk medicine and exotica brought from overseas to Swiss pharmacies since the seventeenth century… The stocks of exotic drugs and objects that colonization brought to early modern pharmacies is quite large too.”

Totelin, Laurence. 2019. “Basel Pharmacy Museum: An Interview.” The Recipes Project. Available here.

For example, Cinchona Bark, (also known as Quinine) a treatment for malaria, was “discovered” by Jesuits in the Andes in 1631. Its treatment made a fortune in Europe and allowed for the further expansion of European powers without the concern for then-deadly disease, malaria. However, Indigenous people knew of the healing properties of the bark before European imperialism; they are not credited with the discovery of the plant, its uses, or a share of the profits made by its development. Today, Roche, a pharmaceutical company in Basel, produces a synthetic version of Quinine.

The Pharmacy Museum and its displays ties directly to —

Museums and Public Institutions:

As noted earlier, many of Basel’s most iconic museums have ties to a colonial past, particularly in how their materials were obtained and displayed. Items were stolen from Indigenous communities under colonial rule (mainly the British and Dutch governments) and then brought back to Switzerland, usually by Swiss scientists and explorers, oftentimes funded by wealthy Swiss families with ties to the triangular trade. Similarly to the colonial history of botany, museum exhibits often hold traces of colonial history and perpetuate the racism of these endeavors in how they are displayed. In Basel, as well as other spaces including Berlin, there is an effort to decolonize museums, returning artifacts to their communities, and provide clearer and comprehensive information on these materials through displays and tours.

Kunstmuseum Basel:

Museum der Kulturen (Museum of Culture):

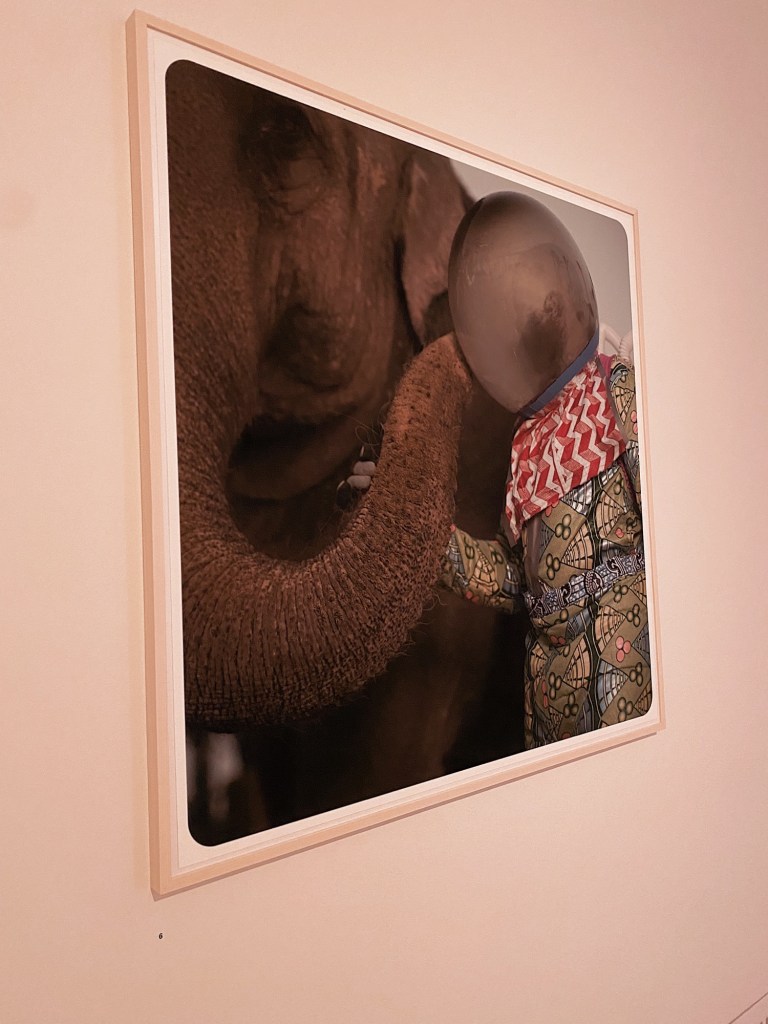

The Museum of Culture was one of the first ethnographic museums in Europe. Scientists including Fritz and Paul Sarasin brought materials from other spaces back to Basel, items that were the early foundation of the museum. Born in the 1850s, Paul and Fritz were born into extremely wealthy families. They both studied medicine and zoology before beginning careers as “gentlemen-naturalists”, traveling to Ceylon (a British colony — present-day-Sri Lanka) and Celebes (a colony of the Dutch East Indies, today-Sulawesi). In Celebes especially, regardless if the cousins were present for scientific purposes, they upheld the colonial ideals of the Dutch, largely ignoring local rulers and communities. Many of their studies on evolution upheld racist hierarchies that placed Europeans at the top of humanity, based largely on the “science” of cranial shape and skin color. The cousins brought thousands of plants and animals, photographs, and 88 human skulls from Celebes and Ceylon to Basel from 1883-1903. Fritz Sarasin was the first director of the museum, followed by his family member, Felix Speiser-Merian.

Spialstrasse 22

Originally built by Emanuel Faesch in 1755 (himself directly involved in colonial trade through his work as an officer in the Dutch army), the Sarasin cousins lived and worked here after returning from the Dutch colonies. Today, the house is used by the University Hospital Basel.

“Museums, in particular Swiss ethnographic museums, more often than not have foundational histories and collections grounded in the 19th century, at the height of European colonial domination. Swiss scientists, missionaries, traders and collectors took advantage of colonized spaces to amass vast collections of ethnographic objects from all over the globe, as well as collecting the human remains of numerous people for scientific racist studies, which they brought back to Switzerland with them.”

Ryser, Vera and Sally Schonfeldt. 2020. “Postcolonial Mnemonics.” A Research and Exhibition Project on Basel’s Colonial History / Theater Basel. Available here.

Basel Zoo:

Source

While I didn’t visit the Basel Zoo during my trip, I do want to mention its history here. Basel Zoo is the oldest in Switzerland, established in 1874. First featuring Swiss animals and flora, the zoo then transitioned to more “exotic” exhibits, including people. Human zoos were extremely popular — Berlin even created its own African district to host its version — and Basel was no different. The Basel Zoo partnered with touring exhibitions (not the people displayed in the zoo) to create a stage of people and animals from particular places. These exhibits were stereotypes and caricatures of life in colonial countries, especially in Africa and South America. Carl Hagenbeck, known as the founder of modern zoos and the people zoos (including Berlin’s), played a role in Basel’s problematic exhibits. Basel Zoo hosted 22 of such exhibits (“Völkerschauen”), 3 of which were planned by Hagenbeck.

“For about 75 years these racist and exploitative exhibitions that also worked as propaganda for the colonist activities by Europeans on other continents, were widely accepted. For the ‘anthropological-zoological’ attractions, people from all over the world were transported to Europe, touring for months through the countries, were paid very badly or not at all and were exposed to medical and mental strains.”

Rohner, Salome. 2020. “Zoo Basel.” Colonial Entanglements in Basel. Available here.

These displays were housed in what is today’s flamingo exhibit. They were highly profitable; in just two to three weeks, the zoo would welcome 20-25% of all its annual visitors to see a visiting human zoo. Similarly to the Sarasin cousins’ work in present day-Sri Lanka, the “Sinhalese” in 1885 showed twelve elephants and fifty people in a mock village. These people were not paid by the zoo, but rather were organized by specific groups that held them under strict control — they were paid little to nothing, could not leave the confines of the exhibit, and often became sick or died from exposure to European diseases. They were also subjected to “scientific” research in addition to being the subject of entertainment for Basel inhabitants. The profits made from these exhibits helped fund the zoo, which was struggling up until 1899. After profits plummeted following WWI, the zoo again held six more shows from 1922-1935, popular events that displayed extremely racist images of humanity.

My Museum Visits:

Kunstmuseum Basel:

Museum of Culture:

“Things and images both convey and trigger memories. We rely on them to bring to mind significant relationships and moments or episodes of our life… In order for them to retain their recollective power, the memories associated with specific keepsakes need to be continuously revised and communicated. Museums may well serve as keepers of things and thus grant them a second life as representatives of the past. But the emotions, memories, and stories associated with them, which could, in theory, restore their singularity, were usually never documented.”

An excerpt from the very descriptive accompanying handout:

“A witch tells a story of conquest, exploitation, and destruction caused by human beings. As her tale unfolds, the spell, the witchery of the story, begins to unleash over the entire existence:

‘Then they grow away from the earth

then they grow away from the sun

then they grow away from the plants and animals.

They see no life.

When they look

they only see objects.

The world is a dead thing for them

the trees and rivers are not alive

the mountains and stones are not alive.

The deer and bear are objects.

They see no life.

They fear

They fear the world.

They destroy what they fear.

They fear themselves.’

— Leslie Marmon Silko (American writer and poet of Laguna Pueblo descent)

What happens when mountains, rivers, trees, animals, mushrooms, things, spirits, ancestors and humans meet? The exhibition focuses on the question of how humans can rethink and change their relationships with other beings in order to find ways out of the planetary crisis.”

Other Sites:

Alstadt (Old Town):

Marktplatz (Market hall):

Basler Münster (Basel Cathedral):

Restaurants & Bakeries:

La Manufacture Elisabethen:

Konditorie-Confiserie Gilgen:

Kaffee Mobil Marktplatz:

Bäckerei KULT:

Bread.Love:

Markthalle Basel:

Mystifry:

Za Zaa:

Backerie KULT:

Shops:

WoMenArt:

Save the Yarn:

❤

Currently:

Reading: Martyr! (Kaveh Akbar)

Watching: Abbott Elementary Season Three (Hulu)

Listening: Cowboy Carter (Beyoncé)

Sources:

Chandrasekhar, Anand. 2019. “The Swiss Textile Industry’s Unsavoury Past.” Swiss Info. Available here.

Dejung, Christof. 2022. “Cosmopolitan Capitalists and Colonial Rule. The Business Structure and Corporate Culture of the Swiss Merchant House Volkart Bros., 1850s-1960s.” Modern Asian Studies 56: 1. 427-470. Available here.

Dijkema, Claske. 2023. “Colonial Entanglements in Basel.” Visioncarto. Available here.

Girardet, Edward. 2021. “Basel’s Uneasy Cross-Border Relationship with Nazi Germany 1933-1945.” Global Geneva. Available here.

Illien, Noele. 2020. “Banking and Slavery: Switzerland Examines its Colonial Conscience.” The Guardian UK. Available here.

Keener, Katherine. 2020. “Kunstmuseum Basel agrees to Settlement Involving Nazi Era Works.” Art Critique. Available here.

Mattioli, Aram. 2001. Jacob Burckhardt and the Limits of Humanity. Library of the Province Publishing House: Munich. 1-88.

Noelle, Nicole. 2023. “On the Trail of Colonialism in Basel.” Kirchenbote. Available here.

Petropoulos, Jonathan. 1997. “Co-Opting Nazi Germany: Neutrality in Europe During World War II.” Anti-Defamation League. Available here.

Pharmaceutical Hub Switzerland. 2022. “Pharmaceutical Hum Switzerland 2022 Basel Region.” Interpharmaph. Available here.

Purtschert, Patricia, Francesca Falk and Barbara Lüthi. 2015. “Switzerland and ‘Colonialism Without Colonies’ Reflections on the Status of Colonial Outsiders.” Interventions. Available here.

Rosh, Benjamin. 2020. “How a A Basel Daigler Traded in Slaves and How his Descendants Wanted to Cover Everything Up.” BZ Basel. Available here.

Ryser, Vera and Sally Schonfeldt. 2020. “Postcolonial Mnemonics.” A Research and Exhibition Project on Basel’s Colonial History / Theater Basel. Available here.

Seroto, Johannes. 2018. “Dynamics of Decoloniality in South Africa: A Critique of the History of Swiss Mission Education for Indigenous People.” Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 44:3. Available here.

Schär, Bernhard C. 2015. “Earth Scientists as Time Travels and Agents of Colonial Conquest: Swiss Naturalists in the Dutch West Indies.” Historical Social Research. 40:2. 67-80. Available here.

This is Basel. 2024. “History.” This is Basel Official Website. Available here.

Totelin, Laurence. 2019. “Basel Pharmacy Museum: An Interview.” The Recipes Project. Available here.

Voirol, Beatrize. 2019. “Decolonization in the Field? Basel – Milingimbi Back and Forth.” Tsantsa # 24. Available here.

Zangger, Andreas. 2020. “How Switzerland Profited from Colonialism.” Swiss Info. Available here.

Zoo Basel. 2024. “People’s Show at Zoo Basel.” Zoo Basel Official Website. Available here.

Leave a comment